Fourth grade should’ve been the hardest year of my early life.

My parents had divorced during the previous summer and sold the house my dad built with his own hands next to a wheat field. Economic opportunity lacking in rural Kansas, we moved to the city of Wichita. After attending the same small-town school from kindergarten through third grade, I started the academic year in the Wichita school district.

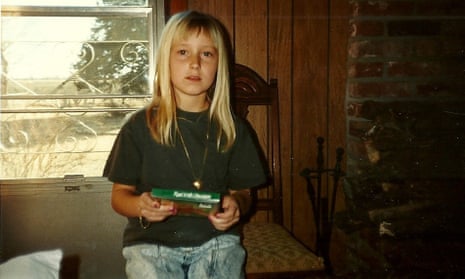

A new school, new place, newly divorced parents with new romantic partners – big challenges for a nine-year-old whose mom and dad were toiling on construction sites and in retail stock rooms, as opposed to volunteering with the parent-teacher association.

Yet this began the happiest period of my childhood: the year and a half when Mr Cheatham was my teacher.

In the basement of our old brick building without air conditioning, where teachers handed out ice chips at the hot start of the school year, Mr Cheatham had built a creative paradise for learning: Art supplies for creating “magazine covers” that bound our writing. A piano to accompany the plays Mr Cheatham – by then a veteran teacher in his 50s, with a thick walrus mustache – wrote for us to perform. A shuffle board court painted on the concrete floor, for practicing math as we kept score. A tent that, with a flashlight shone through it, revealed a night sky of constellations for memorizing. A loft, reached by a wooden ladder, stuffed with bean bags and books.

Mr Cheatham was the teacher designated for advanced learners – an opportunity that hadn’t existed in my previous rural district – and I thus was in his class again in fifth grade.

Around 1990, I wrote my first bit of memoir in his class. I was from a family – midwestern German Catholic farmers – that wasn’t much on reflecting. The demands of labor kept our eyes looking forward toward the next chore, the next bill, and our stoic culture frowned on self-expression.

But Mr Cheatham had assigned us to write a story. For some reason, rather than making something up, I described a scene from my family, embedded with what I longed for someone to know: That my mom was unhappy, that money was tight, that I felt untethered from my home.

Mr Cheatham mailed the raw tale to a national children’s magazine – which published it as a two-page, illustrated spread. No one I knew had ever had their name in a magazine, let alone as the writer.

By the time the story made it into print, I had already changed schools again. Largely owing to the chaos of poverty, I would attend eight schools by the time I finished ninth grade – from a 2,000-student Wichita high school to a creaking two-room schoolhouse on the prairie containing 33 kids.

The winter I left Mr Cheatham’s classroom, my mom took me to the elementary school during holiday break to tell him goodbye. I was wearing a navy wool coat from a discount store and felt embarrassed that my fine blond hair was wild with static from the cold, dry air. It was the last time I saw him.

Around that time – the recent publication of my story an unimaginable joy and validation – I started telling my grandma, who was my primary caretaker for much of my upbringing, that someday I would write a book about our family.

My grandparents left school after sixth and ninth grade to work. In some ways, my family has more in common with the farmers and laborers who often voted against school-district bond issues – proposals to fund school renovations with a small tax increase – than they do with me, a first-generation college graduate and former English professor.

But they have always supported my ambitions and, seeing how education gave me opportunities they never had, are defenders of public education.

“Betsy DeVos is trying to get the Fed government to pay for GUNS for teachers,” my grandma texted me recently. “How insane is that?”

I shared with her that secretary of education DeVos, who would begrudge dollars to public schools and predatory-loan forgiveness to defrauded college students, reportedly owns ten yachts. Someone recently untied one of them, valued at $40 million, from an Ohio dock, setting it adrift on Lake Erie.

“Too bad she wasn’t in it,” Grandma texted back.

The privatization DeVos seeks at the federal level began in my home state years ago. School districts sued the state in 1999 and 2010 for failing to provide adequate funding, the Kansas supreme court repeatedly ruled in their favor, and legislators refused to comply – a constitutional crisis that Democrats and moderate Republicans have fought to resolve by ousting conservative representatives.

Those who profit from the dismantling of public schools do so not just with tax dollars funneled into private school vouchers but with their control over information and ideas. One of the most overlooked threats to democracy is classroom curricula shaped by private interests for their own political, ideological and financial benefit.

The current Kansas gubernatorial race reflects the state’s 20-year school-funding battle. Republican candidate Kris Kobach, best known for helming Donald Trump’s busted voter-fraud commission and for unlawfully suppressing the votes of 30,000 Kansans as secretary of state, has said current public school funding is excessive, evidenced by what he claimed are “Taj Mahal” buildings that “look like Fortune 500 companies”. Meanwhile, Democratic candidate and state senator Laura Kelly, endorsed by the state teachers union, has pledged to be the “education governor” and undo damage wrought by recent governor Sam Brownback’s deep tax cuts.

Whatever their party allegiance, teachers in “red states” like mine aren’t waiting for politicians to save them. Last spring in West Virginia, Oklahoma and Kentucky they went on strike to demand better funding. In this year’s midterm primary elections, Oklahoma educators organized to defeat Republican state House incumbents who voted against raising taxes to fund teacher pay raises. Of the 19 Republicans who voted against the tax increase, eight have been defeated; seven didn’t run; and just four have advanced to the general election.

Amid such a battle over public schools—the sole institution through which our children converge and receive opportunities that most families would not afford in a private system—I sometimes wonder what sort of classroom experience I would have had if born 20 or 30 years later than I was. Teachers are as committed as ever, of course, but the system in which they work has been strategically chipped at, falsely discredited and underfunded since I graduated from high school in the late 1990s.

Those fighting to protect that system are winning. Last spring, the more moderate legislature voted in during the 2016 election approved $500 million in additional funding for Kansas schools, allowing districts to raise teacher salaries and restore cut positions.

Looking back, I see that public school teachers are not just educators but civic soldiers on the frontlines of democracy. They told me I was smart and could be anything – an overreaching statement in a country that has proven to be a plutocracy rather than a meritocracy but one that I believed. Armed with the education and encouragement they had given me, I boldly set my eyes on college, graduate school and the sort of vocation no one from my family had ever known: to get paid for my ideas and creativity rather than for backbreaking or unfulfilling labor.

A book I started writing many years ago, about working-class women, being broke, and the gritty home I love, will be published this month. Mr Cheatham is not just thanked in the acknowledgments but appears in a passage about the crucial role public education played in my life.

He doesn’t know that. He’s 84, and I’ve not seen him in nearly three decades. But recently he appeared on Facebook, commenting about my upcoming book launch at Wichita’s local bookseller, Watermark Books.

There he was, the bushy mustache now thoroughly grayed, in a thumbnail photograph on my laptop screen. There was no “hello” or “it’s been a long time,” as though it was yesterday that I sat in his classroom, when computer screens were green and I had no access to them outside of my public school.

This was all he typed: “I’ll be at Watermark with a story you wrote in 1990.”

Sarah Smarsh’s Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth is out 18 September

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion